In Ann Arbor, the cry “Go Blue!” is heard early and often each autumn, a reference to Michigan’s much-loved maize-and-blue-clad football team. In terms of food history, Zingerman’s imagines “Go Blue!” has been heard in assorted languages all over Europe across history, but in an entirely different, decidedly more funky context.

That’s right, we’re talking about our much loved and often contested friend, blue cheese. More than almost any other type of cheese, Americans seem to either love or hate blue cheese, and many consider blue cheese an acquired taste. Since it’s such a misunderstood cheese, we invite you to learn more about the history and secrets of blue cheese.

First of all, what makes a great blue cheese great? The answer is pretty much all the same things that go into making any cheese great. Top-notch milk taken from animals eating as varied a diet as possible; handmade by skilled cheesemakers; cultured with complex species of mold and matured in caves until the flavor is complex and beautifully balanced. Tradition and history, of course, play a huge role in the birth of blue cheese.

Blue Cheese: Nature & Nurture

More than most other cheese categories, blues are a product of their environment. The Rouergue in France, Darbyshire in England, Lombardy in Italy, and Asturias in Spain were all hotspots for the original blue cheeses, which were almost certainly created by accident. Ever since the early days of cheesemaking, it’s been known that the moist, consistently cool atmospheres of subterranean spaces are ideal for maturing cheeses, especially those that rely on the development of molds for their making. Limestone seems to be particularly prevalent.

While ancient blue cheeses were a product of luck and location, very few these days are still a result of totally natural methods. Today, you can find accomplished blue cheesemakers in Ireland, parts of the U.S., and Denmark. Almost all blue cheese–even the now name-controlled Roquefort, is made using fairly advanced methods which remove much of the mystery and magic and replace it with industrial assurance that the cheese will turn out as planned. Very few blues are made on farms (there are some excellent exceptions to this in Britain and Ireland). In fact, the two best known names in blue cheese, Roquefort and Stilton, are no longer made on farms at all.

Where Does the Blue Come From?

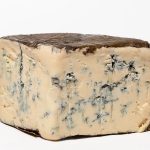

One of blue cheese’s distinguishing factors is its blue veining. What’s the secret? Nothing fancy. Somewhere along in the 19th century someone discovered that the simple step of poking holes into the paste of the cheese would allow for additional oxygen, and hence, enhance the development of the veining. You can see the signs of the needle work, evenly arranged around the outside edge of the cheese. Originally, the holes were made with what were, essentially, knitting needles (Earnest Wagstaff, the since retired Stilton maker at Colston Bassett Dairy, told us they used to use “#9 darning needles”); essentially acupuncture for cheese. Today, the piercing is almost always machine-powered; the wheels are set into small piercing machines which work their magic quickly.

Blue Cheese Beautiful Color Spectrum

Blue cheeses are actually a lot more white, or at least cream-colored, than they are blue. The blue we see is limited to a series of “veins”–collections of caverns, nooks and crannies caused by the development of appropriate molds (more about this in a minute). Take note that the veins in many blue cheeses aren’t actually blue either; rather, they run the color gamut from green to pale blue to indigo.

Roquefort is on the green end of the spectrum; Gorgonzola more of a greenish-blue; Stilton bluish-green; Maytag from Iowa is nearly indigo. The color and frequency of the mold in a blue cheese is one of the factors modern makers now manage in an effort to create a cheese they perceive will be more desirable to the buying public. Most modern Stilton makers now add more mold than they used to, seeking cheeses that are markedly bluer, almost black at times, and ensuring plenty of prominent veining. This they do primarily for visual effect, improved salability, and for easier work on the cutting lines preparing pre-packs for the supermarkets. But in old-style Stiltons, Colston Bassett for example, the veins were much gentler, far less visually striking, a greener shade of blue than what you’d likely be buying in most supermarkets.

Paint your Palate Blue, Taste the Deli’s Best!

In theory, blue cheese is a beautiful thing. But in actual practice, those of us who love it need to deal with the reality that just because a cheese is “blue,” doesn’t mean that it’s necessarily any good. Recipe writers often refer rather generically to “blue cheese.” But of course, there is no single, standard-issue blue, any more than there is a single, standard, “goat cheese.” As they do with any other variety of cheese, the quality and type of milk, the skill of the maker, the recipe, the maturing and adherence to traditional techniques, all make a huge difference in the finished cheese.

To develop your blue cheese palate, find your favorite blues or to give the funky cheese another chance, stop into Zingerman’s Deli to taste across our prized collection of blue cheese to your heart’s content. Our extremely knowledgeable cheesemongers can take you on a tasting tour across the best blue cheeses available today, give you the details on their development and help you develop your palate.